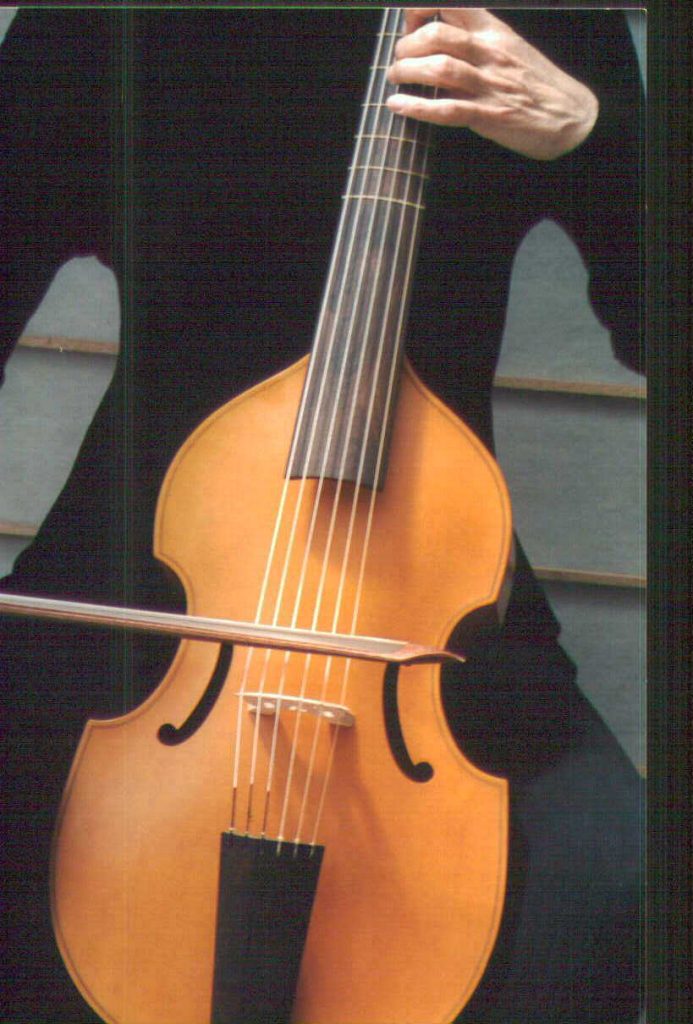

The viola da gamba, or viol, looks like a slope-shouldered cello but is only a distant cousin. Viols were their own family of bowed stringed instruments popular in Renaissance and Baroque Europe. Eclipsed by the rise of modern strings, nearly forgotten during the 19th century, the viol is now back in use around the world by amateur and professional musicians—their gateway to five centuries of great Western music.

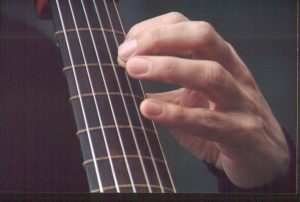

The viol, with guitar-like frets on the neck and six or seven strings (many made of gut), is held between the legs (hence the Italian da gamba, of the leg) and bowed underhand. It is made in a variety of sizes, ranging from the pardessus, which plays in the range of the violin, to a double bass. The cello-size bass has a wide repertory of solo music. The smaller sizes are primarily used for playing in groups of viols, or consorts.

A Singing Instrument

A Victim of History

The bass viol, as a solo or continuo instrument, reigned in the Baroque period. German sacred music made wide use of the viol: J.S. Bach, Telemann, C.P.E. Bach and Buxtehude wrote viol sonatas. In France, Louis XIV and Louis XV employed viol players among their court musicians, and the viol became so fashionable in the salons that even some of the nobles took up playing it. Two fine exponents of French composition and solo playing were the reclusive Monsieur de Saint-Colombe and his student, Marin Marais. Contemporary film audiences will recall their portrayals in the 1992 film Tous les matins du monde, whose soundtrack, played by Jordi Savall, made the European Top 10.

The bass viol, as a solo or continuo instrument, reigned in the Baroque period. German sacred music made wide use of the viol: J.S. Bach, Telemann, C.P.E. Bach and Buxtehude wrote viol sonatas. In France, Louis XIV and Louis XV employed viol players among their court musicians, and the viol became so fashionable in the salons that even some of the nobles took up playing it. Two fine exponents of French composition and solo playing were the reclusive Monsieur de Saint-Colombe and his student, Marin Marais. Contemporary film audiences will recall their portrayals in the 1992 film Tous les matins du monde, whose soundtrack, played by Jordi Savall, made the European Top 10.

Viols were generally too quiet to join the newly developing string orchestra, although they can be heard in J.S. Bach’s Sixth Brandenburg Concerto. Eventually the brighter-sounding violin and cello superseded the viol even in chamber music. And in revolutionary France, the declining viol was seen as a trapping of the hated aristocracy. By 1800 the viol was dismissed as obsolete.

The Viol Revived

Viols languished in closets or musical museums until the late 19th century, when European scholars began rediscovering early music and restoring and recreating period instruments. In the 20th century the increasing popularity of “authentic” performance helped spread the use of the viol among both professionals and amateurs. And recently, contemporary composers have produced a flowering of music for viols.

Viola da Gamba Society of America has just over a thousand members. Here in the Bay Area and other relative hotbeds of viol playing, amateur musicians enjoy monthly coached play days and occasional specialized workshops. Even far-flung viol players can attend an annual national viol convocation, the Conclave, sponsored by VdGSA, held in late July at various locations in the U.S., usually rotating annually among northwest, east, and south.

Viola da Gamba Society of America has just over a thousand members. Here in the Bay Area and other relative hotbeds of viol playing, amateur musicians enjoy monthly coached play days and occasional specialized workshops. Even far-flung viol players can attend an annual national viol convocation, the Conclave, sponsored by VdGSA, held in late July at various locations in the U.S., usually rotating annually among northwest, east, and south.

Many regional workshops flourish, such as Viols West, held in August in San Luis Obispo, California. These gatherings focus on consort playing at all levels, but they also offer classes in technique, older forms of notation, contemporary music, singing with viols, instrument making, and genres not often heard on the viol—jazz, blues, Cajun and mariachi. Viols are also welcome at early music gatherings in general, at living room jam sessions—wherever people make music.

Viols of all sizes can be made to order. Beginners in search of inexpensive instruments can buy them used, or rent them from VdGSA, or our local VdGSA chapter..